대부분의 자료는 위키피디아에서 가져왔음 : https://ko.wikipedia.org https://en.wikipedia.org

하토르

| 하토르 | |||

| 사랑, 아름다움, 모성, 광업, 음악의 신 | |||

소뿔과 태양원반을 쓴 하토르. | |||

| 이름의 신성문자 표기 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 신앙중심지 | 덴데라 | ||

| 상징 | 시스트럼 | ||

| 성별 | 여신 | ||

| 배우자 | 라, 호루스 | ||

| 부모 | 라 | ||

| 형제자매 | 세크메트, 바스테트, 슈, 테프누트, 세르케트 | ||

| 자식 | 이히, 호루스 | ||

하토르(Hathor)는 사랑과 미의 여신이며 오시리스와 이시스의 아들인 호루스의 부인이다. 태양신 라의 딸이며, 하토르가 태양신 라의 벌을 행할 때에는 파괴의 여신 세크메트로 변한다고도 알려져있다. ※ 하토르와 세크메트는 좀 알아둡니다. 이번 <대영박물관전>에 하토르 모양 장신구와 세크메트 거대상이 왔으니.

같이보기[편집]

Hathor (/ˈhæθɔr/ or /ˈhæθər/;[2] Egyptian: ḥwt-ḥr; in Greek: Ἅθωρ, meaning "mansion of Horus")[1] is an Ancient Egyptian goddess who personified the principles of joy, feminine love, and motherhood.[3] She was one of the most important and popular deities throughout the history of Ancient Egypt. Hathor was worshiped by royalty and common people alike in whose tombs she is depicted as "Mistress of the West" welcoming the dead into the next life.[4] In other roles she was a goddess of music, dance, foreign lands and fertility who helped women in childbirth,[4] as well as the patron goddess of miners.[5]

The cult of Hathor predates the historic period, and the roots of devotion to her are therefore difficult to trace, though it may be a development of predynastic cults which venerated fertility, and nature in general, represented by cows.[6]

Hathor is commonly depicted as a cow goddess with horns in which is set a sun disk with Uraeus. Twin feathers are also sometimes shown in later periods as well as a menat necklace.[6] Hathor may be the cow goddess who is depicted from an early date on the Narmer Palette and on a stone urn dating from the 1st dynasty that suggests a role as sky-goddess and a relationship to Horus who, as a sun god, is "housed" in her.[6]

The Ancient Egyptians viewed reality as multi-layered in which deities who merge for various reasons, while retaining divergent attributes and myths, were not seen as contradictory but complementary.[7] In a complicated relationship Hathor is at times the mother, daughter and wife of Ra and, like Isis, is at times described as the mother of Horus, and associated with Bast.[6]

The cult of Osiris promised eternal life to those deemed morally worthy. Originally the justified dead, male or female, became an Osiris but by early Roman times females became identified with Hathor and men with Osiris.[8]

The Ancient Greeks sometimes identified Hathor with the goddess Aphrodite, while in Roman mythology she corresponds to Venus.[9]

Early depictions

Hathor is ambiguously depicted until the 4th dynasty.[10] In the historical era Hathor is shown using the imagery of a cow deity. Artifacts from pre-dynastic times depict cow deities using the same symbolism as used in later times for Hathor and Egyptologists speculate that these deities may be one and the same or precursors to Hathor.[11]

A cow deity appears on the belt of the King on the Narmer Palette dated to the pre-dynastic era, and this may be Hathor or, in another guise, the goddess Bat with whom she is linked and later supplanted. At times they are regarded as one and the same goddess, though likely having separate origins, and reflections of the same divine concept. The evidence pointing to the deity being Hathor in particular is based on a passage from the Pyramid texts which states that the King's apron comes from Hathor.[12]

A stone urn recovered from Hierakonpolis and dated to the first dynasty has on its rim the face of a cow deity with stars on its ears and horns that may relate to Hathor's, or Bat's, role as a sky-goddess.[6] Another artifact from the 1st dynasty shows a cow lying down on an ivory engraving with the inscription "Hathor in the Marshes" indicating her association with vegetation and the papyrus marsh in particular. From the Old Kingdom she was also called Lady of the Sycamore in her capacity as a tree deity.[6]

Relationships, associations, images, and symbols

Hathor had a complex relationship with Ra. At times she is the eye of Ra and considered his daughter, but she is also considered Ra's mother. She absorbed this role from another cow goddess 'Mht wrt' ("Great flood") who was the mother of Ra in a creation myth and carried him between her horns. As a mother she gave birth to Ra each morning on the eastern horizon and as wife she conceives through union with him each day.[6]

Hathor, along with the goddess Nut, was associated with the Milky Way during the third millennium B.C. when, during the fall and spring equinoxes, it aligned over and touched the earth where the sun rose and fell.[13] The four legs of the celestial cow represented Nut or Hathor could, in one account, be seen as the pillars on which the sky was supported with the stars on their bellies constituting the Milky Way on which the solar barque of Ra, representing the sun, sailed.[14]

The Milky Way was seen as a waterway in the heavens, sailed upon by both the sun deity and the moon, leading the ancient Egyptians to describe it as The Nile in the Sky.[15] Due to this, and the name mehturt, she was identified as responsible for the yearly inundation of the Nile. Another consequence of this name is that she was seen as a herald of imminent birth, as when the amniotic sac breaks and floods its waters, it is a medical indicator that the child is due to be born extremely soon. Another interpretation of the Milky Way was that it was the primal snake, Wadjet, the protector of Egypt who was closely associated with Hathor and other early deities among the various aspects of the great mother goddess, including Mut and Naunet. Hathor also was favoured as a protector in desert regions (seeSerabit el-Khadim). As Serabit el-Khadim was where turquoise was mined, Hathor's titles included "Lady of Turquoise", "Mistress of Turquoise", and "Lady of Turquoise Country".[16]

Hathor's identity as a cow, perhaps depicted as such on the Narmer Palette, meant that she became identified with another ancient cow-goddess of fertility, Bat. It still remains an unanswered question amongst Egyptologists as to why Bat survived as an independent goddess for so long. Bat was, in some respects, connected to the Ba, an aspect of the soul, and so Hathor gained an association with the afterlife. It was said that, with her motherly character, Hathor greeted the souls of the dead in Duat, and proffered them with refreshments of food and drink. She also was described sometimes as mistress of the necropolis.

The assimilation of Bat, who was associated with the sistrum, a musical instrument, brought with it an association with music. In this later form, Hathor's cult became centred in Dendera in Upper Egypt and it was led by priestesses and priests who also were dancers, singers and other entertainers.

Hathor also became associated with the menat, the turquoise musical necklace often worn by women. A hymn to Hathor says:

- Thou art the Mistress of Jubilation, the Queen of the Dance, the Mistress of Music, the Queen of the Harp Playing, the Lady of the Choral Dance, the Queen of Wreath Weaving, the Mistress of Inebriety Without End.

Essentially, Hathor had become a goddess of joy, and so she was deeply loved by the general population, and truly revered by women, who aspired to embody her multifaceted role as wife, mother, and lover. In this capacity, she gained the titles of Lady of the House of Jubilation, and The One Who Fills the Sanctuary with Joy. The worship of Hathor was so popular that more festivals were dedicated to her honor than any other Egyptian deity, and more children were named after this goddess than any other deity. Even Hathor's priesthood was unusual, in that both women and men became her priests.

One of the most famous women named after the goddess was Princess Hathorhotep, daughter of King Amenemhat III.[17]

Temples

As Hathor's cult developed from prehistoric cow cults it is not possible to say conclusively where devotion to her first took place. Dendera in Upper Egypt was a significant early site where she was worshiped as "Mistress of Dendera". From the Old Kingdom era she had cult sites in Meir and Kusae with the Giza-Saqqara area perhaps being the centre of devotion. At the start of the first Intermediate period Dendera appears to have become the main cult site where she was considered to be the mother as well as the consort of"Horus of Edfu". Deir el-Bahri, on the west bank of Thebes, was also an important site of Hathor that developed from a pre-existing cow cult.[6]

Temples (and chapels) dedicated to Hathor:

- The Temple of Hathor and Ma'at at Deir el-Medina, West Bank, Luxor.

- The Temple of Hathor at Philae Island, Aswan.

- The Hathor Chapel at the Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut. West Bank, Luxor.

- The temple of Hathor at Timna valley, Israel

Bloodthirsty warrior

The Middle Kingdom was founded when Upper Egypt's pharaoh, Mentuhotep II, took control over Lower Egypt, which had become independent during the First Intermediate Period, by force. This unification had been achieved by a brutal war that was to last some twenty-eight years with many casualties, but when it ceased, calm returned, and the reign of the next pharaoh, Mentuhotep III, was peaceful, and Egypt once again became prosperous. A tale, (see "The Book of the Heavenly Cow"), from the perspective of Lower Egypt, developed around this experience of protracted war. In the tale following the war, Ra (representing the pharaoh of Upper Egypt) was no longer respected by the people (of Lower Egypt) and they ceased to obey his authority.

The myth states that Ra communicated through Hathor's third Eye (Maat) and told her that some people in the land were planning to assassinate him. Hathor was so angry that the people she had created would be audacious enough to plan that she became Sekhmet(war goddess of Upper Egypt) to destroy them. Hathor (as Sekhmet) became bloodthirsty and the slaughter was great because she could not be stopped. As the slaughter continued, Ra saw the chaos down below and decided to stop the blood-thirsty Sekhmet. So he poured huge quantities of blood-coloured beer on the ground to trick Sekhmet. She drank so much of it—thinking it to be blood—that she became drunk and returned to her former gentle self as Hathor.

Hesat

| Hesat in hieroglyphs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ḥsȝt | |||||

In Egyptian mythology, Hesat (also spelt Hesahet, and Hesaret) was the manifestation of Hathor, the divine sky-cow, in earthly form. Like Hathor, she was seen as the wife of Ra.

Since she was the more earthly cow-goddess, milk was said to be the beer of Hesat. As a dairy cow, Hesat was seen as the wet-nurse of the other gods, the one who creates all nourishment. Thus she was pictured as a divine white cow, carrying a tray of food on her horns, with milk flowing from her udders.

In this earthly form, she was, dualistically, said to be the mother of Anubis, the god of the dead, since, it is she, as nourisher, that brings life, and Anubis, as death, that takes it. Since Ra's earthly manifestation was the Mnevis bull, the three of Anubis as son, the Mnevis as father, and Hesat as mother, were identified as a family triad, and worshipped as such.

세크메트

| 세크메트 | |||||

| 불, 전쟁, 복수, 치료, 약물의 신 | |||||

사자머리를 하고 태양 원반과 우라메우스를 머리에 쓴 세크메트. | |||||

| 이름의 신성문자 표기 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 신앙중심지 | 멤피스, 레온토폴리스 | ||||

| 상징 | 태양 원반, 붉은 아마포 | ||||

| 성별 | 여신 | ||||

| 배우자 | 프타 | ||||

| 부모 | 라 | ||||

| 형제자매 | 하토르, 바스테트, 세르케트, 슈, 테프누트 | ||||

세크메트 (Sekhmet, Sachmet, Sakhet, Sekmet, Sakhmet, Sekhet, Sacmis)는 고대 이집트 신화에서 등장하는 암사자 머리를 한 파괴의 여신이다. 이야기에 따라서는 사랑과 미의 여신 하토르와 동일인물로 그려지기도 한다. 반면에 남편인 프타는 창조의 신이다.

※ 이번 <대영박물관전>의 메인 유물 중 하나다. 아주 크고 무거운 조각상이니, 잘 읽어 가면 도움이 될 듯.

개요[편집]

세크메트는 여성적인 힘의 화신이자 전쟁과 복수의 여신으로 암사자의 머리를 하고 있다. 이집트 신화에서는 라가 세상을 파괴하기 위해 세크메트를 만들었으나 마음을 바꾸어 세크메트를 제지하였다고 한다.[1] 세크메트는 인류에게 질병과 재앙을 가져다주는 공포의 여신이었으나, 반면에 추종자들에게는 질병의 치료법을 알려주는 의사의 신이기도 하였다.[2]

세크메트는 라의 눈에서 뿜어져나온 불길에서 탄생하였다고 하며, 남편은 창조의 신 프타였다.[3] 세크메트와 프타의 아들은 향료의 신 네페르템이다.[4]

전투 중에 파라오는 세크메트의 가호를 받는다고 여겨졌다. 고대 이집트인들은 세크메트가 파라오가 땅에 떨어지는 일이 없도록 하고 불화살로 적을 파괴한다고 믿었다. 세크메트는 한 낮의 태양이 내뿜는 불꽃과 같은 빛의 상징이었다. 이때문에 세크메트는 "화염 부인"이라고도 불렸다. 사막의 바람과 함께 작열하는 태양은 당연히 죽음과 파괴의 상징으로 여겨졌을 것이다.[5]

Her cult was so dominant in the culture that when the first pharaoh of the twelfth dynasty, Amenemhat I, moved the capital of Egypt to Itjtawy, the centre for her cult was moved as well. Religion, the royal lineage, and the authority to govern were intrinsically interwoven in Ancient Egypt during its approximately three millennia of existence.

Sekhmet also is a Solar deity, sometimes called the daughter of the sun god Ra and often associated with the goddesses Hathor and Bast. She bears the Solar disk and the uraeus which associates her with Wadjet and royalty. With these associations she can be construed as being a divine arbiter of the goddess Ma'at (Justice, or Order) in the Judgment Hall of Osiris, associating her with the Wadjet (later the Eye of Ra), and connecting her with Tefnut as well.

Sekhmet's name comes from the Ancient Egyptian word "sekhem" which means "power or might". Sekhmet's name suits her function and means "the (one who is) powerful". She also was given titles such as the "(One) Before Whom Evil Trembles", "Mistress of Dread", "Lady of Slaughter" and "She Who Mauls".

History[edit]

In order to placate Sekhmet's wrath, her priestesses performed a ritual before a different statue of the goddess on each day of the year. This practice resulted in many images of the goddess being preserved. Most of her statuettes were rigidly crafted and do not exhibit any expression of movements or dynamism; this design was made to make them last a long time rather than to express any form of functions or actions she is associated with. It is estimated that more than seven hundred statues of Sekhmet once stood in onefunerary temple alone, that of Amenhotep III, on the west bank of the Nile.

She was envisioned as a fierce lioness, and in art, was depicted as such, or as a woman with the head of a lioness, who was dressed in red, the color of blood. Sometimes the dress she wears exhibits a rosetta pattern over each breast, an ancient leonine motif, which can be traced to observation of the shoulder-knot hairs on lions. Occasionally, Sekhmet was also portrayed in her statuettes and engravings with minimal clothing or naked. Tame lions were kept in temples dedicated to Sekhmet atLeontopolis.

Festivals and evolution[edit]

To pacify Sekhmet, festivals were celebrated at the end of battle, so that the destruction would come to an end. During an annual festival held at the beginning of the year, a festival of intoxication, the Egyptians danced and played music to soothe the wildness of the goddess and drank great quantities of wine ritually to imitate the extreme drunkenness that stopped the wrath of the goddess—when she almost destroyed humanity. This may relate to averting excessive flooding during the inundation at the beginning of each year as well, when the Nile ran blood-red with the silt from up-stream and Sekhmet had to swallow the overflow to save humankind.

In 2006, Betsy Bryan, an archaeologist with Johns Hopkins University excavating at the temple of Mut presented her findings about the festival that included illustrations of the priestesses being served to excess and its adverse effects being ministered to by temple attendants.[2] Participation in the festival was great, including the priestesses and the population. Historical records of tens of thousands attending the festival exist. These findings were made in the temple of Mut because when Thebesrose to greater prominence, Mut absorbed some characteristics of Sekhmet. These temple excavations at Luxor discovered a "porch of drunkenness" built onto the temple by the PharaohHatshepsut, during the height of her twenty-year reign.

In a myth about the end of Ra's rule on the earth, Ra sends Hathor or Sekhmet to destroy mortals who conspired against him. In the myth, Sekhmet's blood-lust was not quelled at the end of battle and led to her destroying almost all of humanity, so Ra poured out beer dyed with red ochre or hematite so that it resembled blood. Mistaking the beer for blood, she became so drunk that she gave up the slaughter and returned peacefully to Ra.[3] The same myth was also described in the prognosis texts of the Calendar of Lucky and Unlucky Days of papyrus Cairo 86637, where the actions of Sekhmet, Horus, Ra and Wadjet were connected to the eclipsing binary Algol.[4]

Sekhmet later was considered to be the mother of Maahes, a deity who appeared during the New Kingdom period. He was seen as a lion prince, the son of the goddess. The late origin of Maahes in the Egyptian pantheon may be the incorporation of a Nubian deity of ancient origin in that culture, arriving during trade and warfare or even, during a period of domination by Nubia. During the Greek dominance in Egypt, note was made of a temple for Maahes that was an auxiliary facility to a large temple to Sekhmet at Taremu in the delta region (likely a temple for Bast originally), a city which the Greeks called Leontopolis, where by that time, an enclosure was provided to house lions.

바스테트

The two uniting cultures had deities that shared similar roles and usually the same imagery. In Upper Egypt, Sekhmet was the parallel warrior lioness deity to Bast. Often similar deities merged into one with the unification, but that did not occur with these deities with such strong roots in their cultures. Instead, these goddesses began to diverge. During the Twenty-Second Dynasty (c. 945–715 BC), Bast had changed from a lioness warrior deity into a major protector deity represented as a cat.[2] Bastet, the name associated with this later identity, is the name commonly used by scholars today to refer to this deity.

Name[edit]

Bastet, the form of the name which is most commonly adopted by Egyptologists today because of its use in later dynasties, is a modern convention offering one possible reconstruction. In early Egyptian, her name appears to have been bꜣstt. In Egyptian writing, the second t marks a feminine ending, but was not usually pronounced, and the aleph ꜣ (![]() ) may have moved to a position before the accented syllable, ꜣbst.[3] By the first millennium, then, bꜣstt would have been something like *Ubaste (<*Ubastat) in Egyptian speech, later becoming Coptic Oubaste.[3]

) may have moved to a position before the accented syllable, ꜣbst.[3] By the first millennium, then, bꜣstt would have been something like *Ubaste (<*Ubastat) in Egyptian speech, later becoming Coptic Oubaste.[3]

During later dynasties, Bast was assigned a lesser role in the pantheon bearing the name Bastet, but remained. Thebes became the capital of Ancient Egypt during the 18th Dynasty. As they rose to great power the priests of the temple of Amun, dedicated to the primary local deity, advanced the stature of their titular deity to national prominence and shifted the relative stature of others in the Egyptian pantheon. Diminishing her status, they began referring to Bast with the added suffix, as "Bastet" and their use of the new name was well-documented, becoming very familiar to researchers. By the 22nd dynasty the transition had occurred in all regions.

The town of Bast's cult (see below) was known in Greek as Boubastis (Βούβαστις). The Hebrew rendering of the name for this town is Pî-beset ("House of Bastet"), spelled without Vortonsilbe.[3]

What the name of the goddess means remains uncertain.[3] One recent suggestion by Stephen Quirke (Ancient Egyptian Religion) explains it as meaning "She of the ointment jar". This ties in with the observation that her name was written with the hieroglyph "ointment jar" (bꜣs) and that she was associated with protective ointments, among other things.[3] Also compare the name alabasterwhich might, through Greek, come from the name of the goddess.

She was the goddess of protection against contagious diseases and evil spirits.[4]

아누비스

| 아누비스 | ||||||

| 죽은 자의 수호신이자 시체 방부처리의 신 | ||||||

| ||||||

| 이름의 신성문자 표기 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 신앙중심지 | 아시우트, 키노폴리스 | |||||

| 상징 | 이미우트 주물, 도리깨 | |||||

| 성별 | 남신 | |||||

| 배우자 | 안푸트 | |||||

| 부모 | 라 또는 네프티스와 세트 또는 오시리스 | |||||

| 형제자매 | 호루스, 세베크 | |||||

| 자식 | 케베체트 | |||||

아누비스(Anubis, 이집트어를 라틴어로 옮겨적음:inpu, 고대그리스어:Ἄνουβις)는 이집트 신화에서 망자를 미라의 형태로 만들어 사후세계로 인도하는 신으로서, 자칼의 머리를 하고 있다.

개요[편집]

이집트에서도 ²비교적 오래전부터 숭배되고 있던 신으로, 망자의 신이며 개 또는 자칼의 머리 부분을 가지는 반수의 모습이거나 또는 자칼 그 자체의 모습으로 등장한다. 그 모습은 세트의 모델이 된 동물들과 닮고 있다. 망자의 신이라는 이미지는, 고대 이집트에서 사체의 고기를 요구해 묘지의 주의를 배회하는 개나 자칼의 모습이 마치 망자를 지켜주는 것이라고 착각되어 전해져 왔기 때문이라고 추측한다. 또한 그 몸은 미라를 만들 때에 방부 처리를 위해서 사체에 타르를 바르기 때문에 그와 관련해 검게 표현한다.

이집트 신화[편집]

아누비스는 초기에는 라의 아들로 기록되었으나 이후 네프티스가 어머니, 아버지는 네프티스의 남편인 세트 혹은오시리스이다.

아누비스는 오시리스가 세트에 의해 살해당했을 때에, 그의 시체에 방부 처리를 가했다고 알려져 미라 만들기의 감독관으로 표현된다.[1] 또한 죽은 인간의 혼을 신속하게 명계로 옮겨야 하기 때문에 다리가 매우 빠르다고 여겨진다.

오시리스가 부활해 명계를 지배하게 될 때에도 그를 보좌해 사망자를 인도하는 책임을 지며, 그 모습은 사자의 서나 무덤의 벽면 등에 그려져 있다.

영향[편집]

이집트가 그리스에 병합되었을 때, 이집트 신화와 그리스 미술과의 융합이 발생했다. 바티칸 미술관에는 헬레니즘에 의하여 표현된 아누비스 상이 있다. 인도자로서, 이것을 그리스의 전령의 신 헤르메스와 융합하여 헤르마누비스라고 부른다.

주석[편집]

- ↑ 실제로 미라를 만들거나 사망자를 명계로 이끄는 축사를 내리거나 할 때엔 아누비스의 가면을 쓴 자들(스톰)이 의식을 진행한다.

Anubis is associated with Wepwawet (also called Upuaut), another Egyptian god portrayed with a dog's head or in canine form, but with grey or white fur. Historians assume that the two figures were eventually combined.[9] Anubis' female counterpart is Anput. His daughter is the serpent goddess Kebechet.

Name

"Anubis" is a Greek rendering of this god's Egyptian name.[10][11] In the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 BC – c. 2181 BC), the standard way of writing his name in hieroglyphs was composed of the sound inpw followed by a "jackal"[12] over a ḥtp sign:[13]

A new form with the "jackal" on a tall stand appeared in the late Old Kingdom and became common thereafter:[13]

According to the Akkadian transcription in the Amarna letters, Anubis' name (inpw) was vocalized in Egyptian as Anapa.[14]

History

In Egypt's Early Dynastic period (c. 3100 – c. 2686 BC), Anubis was portrayed in full animal form, with a "jackal" head and body.[15] A "jackal" god, probably Anubis, is depicted in stone inscriptions from the reigns of Hor-Aha, Djer, and other pharaohs of the First Dynasty.[16] Since Predynastic Egypt, when the dead were buried in shallow graves, "jackals" had been strongly associated with cemeteries because they were scavengers which uncovered human bodies and ate their flesh.[17] In the spirit of "fighting like with like," a "jackal" was chosen to protect the dead, because "a common problem (and cause of concern) must have been the digging up of bodies, shortly after burial, by jackals and other wild dogs which lived on the margins of the cultivation."[18]

The oldest known textual mention of Anubis is in the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom (c. 2686 – c. 2181 BC), where he is associated with the burial of the pharaoh.[19]

In the Old Kingdom, Anubis was the most important god of the dead. He was replaced in that role by Osiris during the Middle Kingdom (2000–1700 BC).[20] In the Roman era, which started in 30 BC, tomb paintings depict him holding the hand of deceased persons to guide them to Osiris.[21]

The parentage of Anubis varied between myths, times and sources. In early mythology, he was portrayed as a son of Ra.[22] In the Coffin Texts, which were written in the First Intermediate Period (c. 2181–2055 BC), Anubis is the son of either the cow goddess Hesat or the cat-headed Bastet.[23] Another tradition depicted him as the son of his father Ra and mother Nephthys.[22] The Greek Plutarch (c. 40–120 AD) stated that Anubis was the illegitimate son of Nephthys and Osiris, but that he was adopted by Osiris's wifeIsis:[24]

George Hart sees this story as an "attempt to incorporate the independent deity Anubis into the Osirian pantheon."[23] An Egyptian papyrus from the Roman period (30–380 AD) simply called Anubis the "son of Isis."[23]

In the Ptolemaic period (350–30 BC), when Egypt became a Hellenistic kingdom ruled by Greek pharaohs, Anubis was merged with theGreek god Hermes, becoming Hermanubis.[25][26] The two gods were considered similar because they both guided souls to the afterlife.[27]The center of this cult was in uten-ha/Sa-ka/ Cynopolis, a place whose Greek name means "city of dogs." In Book XI of The Golden Ass byApuleius, there is evidence that the worship of this god was continued in Rome through at least the 2nd century. Indeed, Hermanubis also appears in the alchemical and hermetical literature of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

Although the Greeks and Romans typically scorned Egypt's animal-headed gods as bizarre and primitive (Anubis was mockingly called "Barker" by the Greeks), Anubis was sometimes associated with Sirius in the heavens and Cerberus and Hades in the underworld. [28] In his dialogues, Plato often has Socrates utter oaths "by the dog" (kai me ton kuna), "by the dog of Egypt", and "by the dog, the god of the Egyptians", both for emphasis and to appeal to Anubis as an arbiter of truth in the underworld.[29]

Roles

Protector of tombs

In contrast to real wolves, Anubis was a protector of graves and cemeteries. Several epithets attached to his name in Egyptian texts and inscriptions referred to that role.Khenty-imentiu, which means "foremost of the westerners" and later became the name of a different wolf god, alluded to his protecting function because the dead were usually buried on the west bank of the Nile.[30] He took other names in connection with his funerary role, such as "He who is upon his mountain" (tepy-dju-ef) – keeping guard over tombs from above – and "Lord of the sacred land" (neb-ta-djeser), which designates him as a god of the desert necropolis.[31]

Most ancient tombs had prayers to Anubis carved on them.[32]

Embalmer

As "He who is in the place of embalming" (imy-ut), Anubis was associated with mummification. He was also called "He who presides over the god's pavilion" (khanty-she-netjer), in which "pavilion" could be refer either to the place where embalming was carried out, or the pharaoh's burial chamber.[31]

In the Osiris myth, Anubis helped Isis to embalm Osiris.[20] Indeed, when the Osiris myth emerged, it was said that after Osiris had been killed by Set, Osiris's organs were given to Anubis as a gift. With this connection, Anubis became the patron god of embalmers; during the rites of mummification, illustrations from the Book of the Dead often show a wolf-mask-wearing priest supporting the upright mummy.

Guide of souls

By the late pharaonic era (664–332 BC), Anubis was often depicted as guiding individuals across the threshold from the world of the living to the afterlife.[33] Though a similar role was sometimes performed by the cow-headed Hathor, Anubis was more commonly chosen to fulfill that function.[34] Greek writers from the Roman period of Egyptian history designated that role as that of "psychopomp", a Greek term meaning "guide of souls" that they used to refer to their own god Hermes, who also played that role inGreek religion.[27] Funerary art from that period represents Anubis guiding either men or women dressed in Greek clothes into the presence of Osiris, who by then had long replaced Anubis as ruler of the underworld.[35]

Weighing of the heart

One of the roles of Anubis was as the "Guardian of the Scales."[36] The critical scene depicting the weighing of the heart, in the Book of the Dead, shows Anubis performing a measurement that determined whether the person was worthy of entering the realm of the dead (the underworld, known as Duat). By weighing the heart of a deceased person against Ma'at (or "truth"), who was often represented as an ostrich feather, Anubis dictated the fate of souls. Souls heavier than a feather would be devoured by Ammit, and souls lighter than a feather would ascend to a heavenly existence.[37][38]

Portrayal in art

Anubis was one of the most frequently represented gods in ancient Egyptian art.[8] In the early dynastic period, he was depicted in animal form, as a black wolf.[39] Anubis's distinctive black color did not represent the coat of real wolves, but it had several symbolic meanings.[40] First it represented "the discolouration of the corpse after its treatment with natron and the smearing of the wrappings with a resinous substance during mummification".[40] Being the color of the fertile silt of the River Nile, to Egyptians black also symbolized fertility and the possibility of rebirth in the afterlife.[41]

Later[when?] Anubis was often portrayed as a wolf-headed human.[42] An extremely rare depiction of him in fully human form was found in the tomb of Ramesses II in Abydos.[40][11]

Anubis is often depicted wearing a ribbon and holding a nekhakha "flail" in the crook of his arm.[42] Another of Anubis's attributes was the Imiut fetish.[43]

In funerary contexts, Anubis is shown either attending to a deceased person's mummy or sitting atop a tomb protecting it. New Kingdom tomb-seals also depict Anubis sitting atop the nine bows that symbolize his domination over the enemies of Egypt

세베크

| 세베크 | |||||||

| 나일 강, 군대, 군사, 풍요의 신 | |||||||

| |||||||

| 이름의 신성문자 표기 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 신앙중심지 | 파이윰, 콤 옴보, 크로코딜로폴리스 | ||||||

| 상징 | 크로코다일 | ||||||

| 부모 | 네이트 | ||||||

세베크(Sebek), 또는 소베크(Sobek)는 악어가 신격화된 이집트 신으로, 나일 강에 의존하던 이집트에서 악어를 매우 두려워하던 것에서 기인하였다. 나일 강에서 일을 하거나 여행을 하는 이집트인들은 악어의 신 세베크에게 기도하여, 악어에게 공격 받지 않도록 그가 자신을 보호해주기를 소망하였다.[1] 세베크는 악어, 또는 악어의 머리를 한 남자로 묘사되었으며, 강력한 공포의 신이었다. 일부 이집트 창조 신화에서는 세베크가 세상을 창조하는 혼돈의 물에서 처음으로 나왔다고 묘사한다.[1] 때때로 창조신의 모습으로 태양신 레와 연결되기도 한다.[1]

주석[편집]

The origin of his name, Sbk[5] in ancient Egyptian, is debated among scholars, but many believe that it is derived from a causative of the verb "to impregnate".[6]

Though Sobek was worshipped in the Old Kingdom, he truly gained prominence in the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BCE), most notably under the Twelfth Dynasty king, Amenemhat III. Amenemhat III had taken a particular interest in the Faiyum region of Egypt, a region heavily associated with Sobek. Amenemhat and many of his dynastic contemporaries engaged in building projects to promote Sobek – projects that were often executed in the Faiyum. In this period, Sobek also underwent an important change: he was often fused with the falcon-headed god of divine kingship, Horus. This brought Sobek even closer with the kings of Egypt, thereby giving him a place of greater prominence in the Egyptian pantheon.[7] The fusion added a finer level of complexity to the god’s nature, as he was adopted into the divine triad of Horus and his two parents: Osiris and Isis.[8]

Sobek first acquired a role as a solar deity through his connection to Horus, but this was further strengthened in later periods with the emergence of Sobek-Ra, a fusion of Sobek and Egypt's primary sun god, Ra. Sobek-Horus persisted as a figure in the New Kingdom(1550–1069 BCE), but it was not until the last dynasties of Egypt that Sobek-Ra gained prominence. This understanding of the god was maintained after the fall of Egypt's last native dynasty in Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt (c. 332 BCE – 390 CE). The prestige of both Sobek and Sobek-Ra endured in this time period and tributes to him attained greater prominence – both through the expansion of his dedicated cultic sites and a concerted scholarly effort to make him the subject of religious doctrine.[9]

세케르

Seker

- For the name, see Şeker.

- For the places in Azerbaijan, see Şəkər.

- For the Stargate SG-1 character, see Sokar (Stargate)

| Seker in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Seker (/ˈsɛkər/; also spelled Sokar) is a falcon god of the Memphite necropolis. Although the meaning of his name remains uncertain, the Egyptians in the Pyramid Texts linked his name to the anguished cry of Osiris to Isis 'Sy-k-ri' ('hurry to me'),[1] in the underworld. Seker is strongly linked with two other gods, Ptah the Creator god and chief god of Memphis and Osiris the god of the dead. In later periods this connection was expressed as the triple god Ptah-Seker-Osiris.

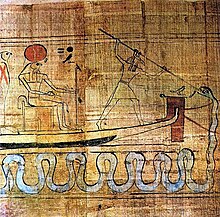

Seker was usually depicted as a mummified hawk and sometimes as mound from which the head of a hawk appears. Here he is called 'he who is on his sand'. Sometimes he is shown on his hennu barque which was an elaborate sledge for negotiating the sandy necropolis. One of his titles was 'He of Restau' which means the place of 'openings' or tomb entrances.

In the New Kingdom Book of the Underworld, the Amduat, he is shown standing on the back of a serpent between two spread wings; as an expression of freedom this suggests a connection with resurrection or perhaps a satisfactory transit of the underworld.[1] Despite this the region of the underworld associated with Seker was seen as difficult, sandy terrain called the Imhet (meaning 'filled up').[2]

Seker, possibly through his association with Ptah, also has a connection with craftsmen. In the Book of the Dead he is said to fashion silver bowls[1] and a silver coffin of Sheshonq II has been discovered at Tanis decorated with the iconography of Seker.[3] Seker's cult centre was in Memphis where festivals in his honour were held in the fourth month of the akhet (spring) season. The god was depicted as assisting in various tasks such as digging ditches and canals. From the New Kingdom a similar festival was held in Thebes.[3]

Popular culture

In the 1956 movie The Ten Commandments, the Pharaoh Rameses II invokes the same deity to bring his deceased firstborn son back to life, while portrayed as wearing dark blue robe with a silver bow.

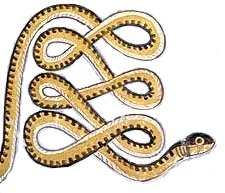

아펩

아펩(Apep, Apepi, Aapep, Apophis)은 고대 이집트 신화에 등장하는 뱀의 모습을 한 악의 신이다. 태양신 라가 태양의 돛단배를 타고 두아트로 넘어가는 계곡에 있다고 전해지며, 태양신 라는 아펩과 싸워 승리한다. 여기서 아펩은 혼돈과 어둠을 상징하며, 라는 질서와 빛, 정의를 상징한다.

Development[edit]

| Apep in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Ra was the solar deity, bringer of light, and thus the upholder of Ma'at. Apep was viewed as the greatest enemy of Ra, and thus was given the title Enemy of Ra, and also "the Lord of Chaos".

As the personification of all that was evil, Apep was seen as a giant snake or serpent leading to such titles as Serpent from the Nile and Evil Lizard. Some elaborations said that he stretched 16 yards in length and had a head made of flint. Already on a Naqada I (ca. 4000 BC) C-ware bowl (now in Cairo) a snake was painted on the inside rim combined with other desert and aquatic animals as a possible enemy of a deity, possibly a solar deity, who is invisibly hunting in a big rowing vessel.[3]

Also, comparable hostile snakes as enemies of the sun god existed under other names (in the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts) already before the name Apep occurred. The etymology of his name (ꜥꜣpp) is perhaps to be sought in some west-semitic language where a word root ꜣpp meaning 'to slither' existed. A verb root ꜥꜣpp does at any rate not exist elsewhere in Ancient Egyptian. (It is not to be confused with the verb ꜥpı͗/ꜥpp: 'to fly across the sky, to travel') Apep's name much later came to be falsely connected etymologically in Egyptian with a different root meaning (he who was) spat out; the Romans referred to Apep by this translation of his name. Apophis was a large golden snake known to be miles long. He was so large that he attempted to swallow the sun every day.

Battles with Ra[edit]

Tales of Apep's battles against Ra were elaborated during the New Kingdom.[5] Since everyone can see that the sun is not attacked by a giant snake during the day, every day, storytellers said that Apep must lie just below the horizon. This appropriately made him a part of the underworld. In some stories Apep waited for Ra in a western mountain called Bakhu, where the sun set, and in others Apep lurked just before dawn, in the Tenth region of the Night. The wide range of Apep's possible location gained him the title World Encircler. It was thought that his terrifying roar would cause the underworld to rumble. Myths sometimes say that Apep was trapped there, because he had been the previous chief god overthrown by Ra, or because he was evil and had been imprisoned.

The Coffin Texts imply that Apep used a magical gaze to overwhelm Ra and his entourage.[6] Ra was assisted by a number of defenders who travelled with him, including Set and possibly the Eye of Ra.[7] Apep's movements were thought to cause earthquakes, and his battles with Set may have been meant to explain the origin of thunderstorms. In some accounts, Ra himself defeats Apep in the form of a cat.[8]

Worship[edit]

Ra was worshipped, and Apep worshipped against. Ra's victory each night was thought to be ensured by the prayers of the Egyptian priestsand worshippers at temples. The Egyptians practiced a number of rituals and superstitions that were thought to ward off Apep, and aid Ra to continue his journey across the sky.

In an annual rite, called the Banishing of Chaos, priests would build an effigy of Apep that was thought to contain all of the evil and darkness in Egypt, and burn it to protect everyone from Apep's evil for another year, in a similar manner to modern rituals such as Zozobra.

The Egyptian priests had a detailed guide to fighting Apep, referred to as The Books of Overthrowing Apep (or the Book of Apophis, in Greek).[9] The chapters described a gradual process of dismemberment and disposal, and include:

In addition to stories about Ra's winnings, this guide had instructions for making wax models, or small drawings, of the serpent, which would be spat on, mutilated and burnt, whilst reciting spells that would kill Apep. Fearing that even the image of Apep could give power to the demon any rendering would always include another deity to subdue the monster.

As Apep was thought to live in the underworld, he was sometimes thought of as an Eater of Souls. Thus the dead also needed protection, so they were sometimes buried with spells that could destroy Apep. The Book of the Dead does not frequently describe occasions when Ra defeated the chaos snake explicitly called Apep. Only BD Spells 7 and 39 can be explained as such.[10]

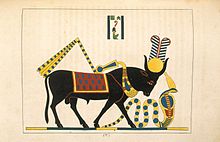

아피스

아피스 (Apis, Hapis, Hapi-ankh)는 고대 이집트 멤피스지역에서 숭배 받던 성스러운 소이다. 아피스 소에 대한 숭배는 제2왕조 때부터 시작된 것으로 보인다. 아피스는 이집트 전역에 있는 소들 중 특별한 무늬를 기준으로 선별되었으며, 소가 죽으면 성대한 장례의식을 취하고 같은 무늬가 있는 소를 다시 찾아 부활한 아피스로 모셨다.

n Egyptian mythology, Apis or Hapis (alternatively spelled Hapi-ankh) is a bull-deity that was worshipped in the Memphisregion. "Apis served as an intermediary between humans and an all-powerful god (originally Ptah, later Osiris, then Atum)." [quote: Virtual Egyptian Museum]

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

| Ancient Egypt portal |

Apis was the most important of all the sacred animals in Egypt, and, as with the others, its importance increased as time went on. Greek and Roman authors have much to say about Apis, the marks by which the black bull-calf was recognized, the manner of his conception by a ray from heaven, his house at Memphis with court for disporting himself, the mode of prognostication from his actions, the mourning at his death, his costly burial, and the rejoicings throughout the country when a new Apis was found.Auguste Mariette's excavation of the Serapeum at Memphis revealed the tombs of over sixty animals, ranging from the time ofAmenophis III to that of Ptolemy Alexander. At first each animal was buried in a separate tomb with a chapel built above it.

History of worship[edit]

The cult of the Apis bull started at the very beginning of Egyptian history, probably as a fertility god connected to grain and the herds[citation needed]. According to Manetho, his worship was instituted by Kaiechos of the Second Dynasty. Apis is named on very early monuments, but little is known of the divine animal before the New Kingdom. Ceremonial burials of bulls indicate that ritual sacrifice was part of the worship of the early cow deities and a bull might represent a king who became a deity after death. He was entitled "the renewal of the life" of the Memphite god Ptah: but after death he became Osorapis, i.e. the Osiris Apis, just as dead humans were assimilated to Osiris, the king of the underworld. This Osorapis was identified with the Hellenistic Serapis, and may well be identical with him. Greek writers make the Apis an incarnation of Osiris, ignoring the connection with Ptah.

Apis was the most popular of the three great bull cults of ancient Egypt (the others being the bulls Mnevis and Buchis.) The worship of the Apis bull was continued by the Greeks and after them by the Romans, and lasted until almost 400 A.D.

Herald of Ptah[edit]

This animal was chosen because it symbolized the king’s courageous heart, great strength, virility, and fighting spirit. The Apis bull was considered to be a manifestation of the pharaoh, as bulls were symbols of strength and fertility, qualities which are closely linked with kingship ("strong bull of his mother Hathor" was a common title for gods and pharaohs).

Occasionally, the Apis bull was pictured with her sun-disk between his horns, being one of few deities associated with her symbol. When the disk was depicted on his head with his horns below and the triangle on his forehead, an ankh was suggested. It also is a symbol closely associated with his mother.

Apis was originally the Herald (wHm) of Ptah, the chief god in the area around Memphis. As a manifestation of Ptah, Apis also was considered to be a symbol of the pharaoh, embodying the qualities of kingship.

The bovines in the region in which Ptah was worshipped exhibited white patterning on their mainly black bodies, and so a belief grew up that the Apis bull had to have a certain set of markings suitable to its role. It was required to have a white triangle upon its forehead, a white vulture wing outline on its back, a scarab mark under its tongue, a white crescent moon shape on its right flank, and double hairs on its tail.

The bull which matched these markings was selected from the herd, brought to a temple, given a harem of cows, and worshipped as an aspect of Ptah. His mother was believed to have been conceived by a flash of lightning from the heavens, or from moonbeams, and also was treated specially. At the temple, Apis was used as an oracle, his movements being interpreted as prophecies. His breath was believed to cure disease, and his presence to bless those around with virility. He was given a window in the temple through which he could be seen, and on certain holidays was led through the streets of the city, bedecked with jewelry and flowers.

Burial[edit]

Details of the mummification ritual of the sacred bull are written within the Apis papyrus. [1] Sometimes the body of the bull wasmummified and fixed in a standing position on a foundation made of wooden planks.

By the New Kingdom, the remains of the Apis bulls were interred at the cemetery of Saqqara. The earliest known burial in Saqqara was performed in the reign of Amenhotep III by his son Thutmosis; afterwards, seven more bulls were buried nearby. Ramesses II initiated Apis burials in what is now known as the Serapeum, an underground complex of burial chambers at Saqqara for the sacred bulls, a site used through the rest of Egyptian history into the reign of Cleopatra VII.

Khamuis, the priestly son of Ramesses II (c. 1300 B.C.), excavated a great gallery to be lined with the tomb chambers; another similar gallery was added by Psammetichus I. The careful statement of the ages of the animals in the later instances, with the regnal dates for their birth, enthronement, and death have thrown much light on the chronology from the Twenty-second dynasty onwards. The name of the mother-cow and the place of birth often are recorded. The sarcophagi are of immense size, and the burial must have entailed enormous expense. It is therefore remarkable that the priests contrived to bury one of the animals in the fourth year of Cambyses.

The Apis was a protector of the deceased and linked to the pharaoh. Bulls' horns embellish some of the tombs of ancient pharaohs, and the Apis bull was often depicted on private coffins as a powerful protector. As a form of Osiris, lord of the dead, it was believed that to be under the protection of the Apis bull would give the person control over the four winds in the afterlife.

From bull to man[edit]

According to Arrian, Apis was one of the Egyptian Gods for which Alexander the Great performed a sacrifice during his seizure of the country from the Persians.[3] After Alexander's death, his general Ptolemy Soter made efforts to integrate Egyptian religion with that of their new Hellenic rulers. Ptolemy's policy was to find a deity that should win the reverence alike of both groups, despite the curses of the Egyptian priests against the gods of the previous foreign rulers (i.e. Set who was lauded by the Hyksos). Alexander had attempted to use Amun for this purpose, but he was more prominent in Upper Egypt, which was not so popular with those in Lower Egypt, where the Greeks had stronger influence. Nevertheless, the Greeks had little respect for animal-headed figures, and so a Greek statue was chosen as the idol, and proclaimed as anthropomorphic equivalent of the highly popular Apis. It was namedAser-hapi (i.e. Osiris-Apis), which became Serapis, and was said to be Osiris in full, rather than just his Ka.

The earliest mention of a Serapis is in the authentic death scene of Alexander, from the royal diaries.[4] Here, Serapis has a temple at Babylon, and is of such importance that he alone is named as being consulted on behalf of the dying king. His presence in Babylon would radically alter perceptions of the mythologies of this era, though fortunately, it has been discovered that the unconnected Babylonian god Ea was titled Serapsi, meaning king of the deep, and it is this Serapsi which is referred to in the diaries. The significance of this Serapsi in the Hellenic psyche, due to its involvement in Alexander's death, may have also contributed to the choice of Osiris-Apis as the chief Ptolemaic god.

According to Plutarch, Ptolemy stole the statue from Sinope, having been instructed in a dream by the unknown god, to bring the statue to Alexandria, where the statue was pronounced to be Serapis by two religious experts. One of the experts was one of the Eumolpidae, the ancient family from whose members the hierophant of the Eleusinian Mysteries had been chosen since before history, and the other was the scholarly Egyptian priest Manetho, which gave weight to the judgement both for the Egyptians and the Greeks.

Plutarch may not however be correct, as some Egyptologists allege that the Sinope in the tale is really the hill of Sinopeion, a name given to the site of the already existing Serapeum at Memphis. Also, according to Tacitus, Serapis (i.e. Apis explicitly identified as Osiris in full) had been the god of the village of Rhacotis, before it suddenly expanded into the great capital of Alexandria.

The statue suitably depicted a figure resembling Hades or Pluto, both being kings of the Greek underworld, and was shown enthroned with the modius, which is a basket/grain-measure, on his head, since it was a Greek symbol for the land of the dead. He also held asceptre in his hand indicating his rulership, with Cerberus, gatekeeper of the underworld, resting at his feet, and it also had what appeared to be a serpent at its base, fitting the Egyptian symbol of rulership, the uraeus.

With his (i.e., Osiris') wife, Isis, and their son (at this point in history) Horus (in the form of Harpocrates), Serapis won an important place in the Greek world, reaching Ancient Rome, with Anubis being identified as Cerberus. The cult survived until 385 AD, when Christians destroyed the Serapeum of Alexandria, and subsequently the cult was forbidden by the Theodosian decree.

| 신성 문자로 쓴 아피스의 공통 표기 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|