거의 모든 정보는 위키피디아에서 데려옴 : https://ko.wikipedia.org https://en.wikipedia.org

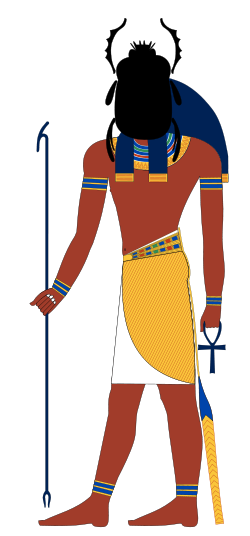

크눔

Khnum (/kəˈnuːm/; also spelled Khnemu) was one of the earliest Egyptian deities, originally the god of the source of the Nile River. Since the annual flooding of the Nile brought with it silt and clay, and its water brought life to its surroundings, he was thought to be the creator of the bodies of human children, which he made at a potter's wheel, from clay, and placed in their mothers' wombs. He later was described as having moulded the other deities, and he had the titles Divine Potter and Lord of created things from himself.

General information[edit]

Khnum is the third aspect of Ra. He is the god of rebirth, creation and the evening sun, although this is usually the function of Atum. The worship of Khnum centered on two principal riverside sites, Elephantine Island and Esna, which were regarded as sacred sites. At Elephantine, he was worshipped alongside Anuket and Satis as the guardian of the source of the Nile River. His significance led to early theophoric names of him, for children, such as Khnum-Khufwy – Khnum is my Protector, the full name of Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid.[1]

Khnum has also been related to the deity Min.[2]

Temple at Elephantine[edit]

The temple at Elephantine was dedicated to Khnum, his consort Satis and their daughter Anukis. The temple dates back to at least the Middle Kingdom. By the 11th dynasty Khnum, Satis and Anukis are all attested at Elephantine. During the New Kingdom finds from the time of Ramesses II show Khnum was still worshipped there.[3]

Opposite Elephantine, on the east bank at Aswan, Khnum, Satis and Anukis are shown on a chapel wall dating to the Ptolemaic time.[3]

Temple at Esna[edit]

In Esna (Latopolis), known as Iunyt or Ta-senet to the Ancient Egyptians, a temple was dedicated to Khnum, Neith and Heka, and other deities.[3] The temple dates to the Ptolemaic period. Khnum is sometimes depicted as a crocodile-headed god. Nebt-uu and Menhit are Khnum's principal consorts and Heka is his eldest son and successor. Both Khnum and Neith are referred to as creator deities in the texts at Esna. Khnum is sometimes referred to as the "father of the fathers" and Neith as the "mother of the mothers". They later become the parents of Re, who is also referred to as Khnum-Re.[4]

Other[edit]

The Beit el-Wali temple of Ramesses II contained statues of Khnum, Satis and Anukis, along with statues of Isis and Horus.[3]

In other locations, such as Herwer (Tuna el-Gebel perhaps), as the moulder and creator of the human body, he was sometimes regarded as the consort of Heket, or of Meskhenet, whose responsibility was breathing life into children at the moment of birth, as theKa.[citation needed]

Artistic conventions[edit]

In art, he was usually depicted as a ram-headed man at a potter's wheel, with recently created children's bodies standing on the wheel, although he also appeared in his earlier guise as a water-god, holding a jar from which flowed a stream of water. However, he occasionally appeared in a compound image, depicting the elements, in which he, representing water, was shown as one of four heads of a man, with the others being, – Geb representing earth, Shu representing the air, and Osiris representing death.

| Nun | Mehet-Weret | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ra | Maat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shu | Tefnut | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Geb | Nut | Thoth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isis | Osiris | Nephthys | Seth | Neith | Khnum | Satet | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus | Anubis | Anput | Sobek | Apep | Anuket | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Four sons of Horus | Kebechet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

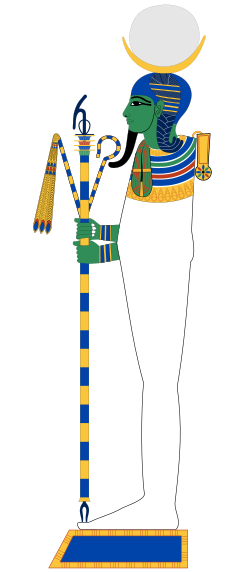

케프리

| 케프리 | |||||

| 재생, 일출의 신 | |||||

케프리는 쇠똥구리 머리를 한 남성, 또는 태양을 치켜들고 있는 쇠똥구리의 모습으로 그려진다. | |||||

| 이름의 신성문자 표기 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 신앙중심지 | 헬리오폴리스 | ||||

| 상징 | 쇠똥구리, 수련꽃 | ||||

| 성별 | 남신 | ||||

| 형제자매 | 아툼, 라 | ||||

케프리 (Khepri, Khepera, Kheper, Chepri, Khepra)는 고대 이집트 신화의 태양신이다. 이집트의 태양신은 아침에는 케프리, 낮에는 라, 저녁에는 아툼이라고 불렀다.

Symbolism

Khepri was connected with the scarab beetle (kheprer), because the scarab rolls balls of dung across the ground, an act that the Egyptians saw as a symbol of the forces that move the sun across the sky. Khepri was thus a solar deity. Young dung beetles, having been laid as eggs within the dung ball, emerge from it fully formed. Therefore, Khepri also represented creation and rebirth, and he was specifically connected with the rising sun and the mythical creation of the world. The Egyptians connected his name with the Egyptian language verb kheper, meaning "develop" or "come into being".[1] Kheper, (or Xeper) is a transcription of an ancient Egyptian word meaning to come into being, to change, to occur, to happen, to exist, to bring about, to create, etc. Egyptologists typically transliterate the word as ?pr. Both Kheper and Xeper possess the same phonetic value and are pronounced as "kheffer".

Religion

There was no cult devoted to Khepri, and he was largely subordinate to the greater sun god Ra. Often, Khepri and another solar deity, Atum, were seen as aspects of Ra: Khepri was the morning sun, Ra was the midday sun, and Atum was the sun in the evening.[1]

Appearance

Khepri was principally depicted as a scarab beetle, though in some tomb paintings and funerary papyri he is represented as a human male with a scarab as a head. He is also depicted as a scarab in a solar barque held aloft by Nun. The scarab amulets that the Egyptians used as jewelry and as seals represent Khepri.[2]

※ 형제가 아니라 같은 신격일 텐데.

아톤

| 아톤 | |||||

| 햇살의 신 | |||||

아톤은 햇살이 뻗어나오는 태양 그 자체로 그려진다. | |||||

| 이름의 신성문자 표기 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

아톤 (Aton, Aten)은 본래 태양의 빛, 햇살을 의미하는 신이었으나 고대 이집트의 파라오 아크나톤이 창시한 종교의 유일신이 되었다.

기원[편집]

원래는 석양을 신격화 한 신으로, 테베에서 모셔지고 있었[1]지만, 작은 지방신의 하나에 지나지 않고, 이렇다 할 만한 신상도 신화도 없고, 어떤 신인지, 뚜렷한 성질도 갖지 않았다. 그 때문에 당초부터 사람들의 해석으로서는 석양의 신인 것부터, 태양신 라와 동일시 되었지만, 별로 신앙은 분위기가 살지 않고, 후에는 신성이 희미해지고, 천체로서의 태양을 나타내게 되어 갔다.

아마르나 혁명[편집]

종교개혁의 개시[편집]

아멘호테프 4세의 왕비 네페르티티는 아텐 신[2]을 신앙하고 있었다. 왕비의 영향도 있어 아멘호테프 4세도 아텐 신을 신앙하고 있었다. 한편, 당시 이집트에서 신앙을 모으고 있던 것은 아텐 신이 아니고, 구래의 태양신 아멘에서 만났다.(아문) 아멘호테프 4세의 치세에서 아멘 신앙은 전성기를 맞이하고 아멘을 칭송하고 있던 이집트의 신관들(아멘신단)은 파라오도 견디는 권세를 자랑했다. 아멘호테프 4세는 아멘신단을 억압해 왕권을 강화하려는 목적으로, 자신의 이름도 「아크엔아텐」으로 고쳐 아멘신의 문자를 깎았다. 왕가로서의 아멘 신앙을 정지해, 아텐 신앙을 가지고 이것으로 바꾼 것이다, 다른 신들의 제사를 정지했기 때문에, 다신교는 아니고 일신교의 양상을 나타내기에 이르렀다. 이것을 「아마르나 종교개혁」또는 「아마르나 혁명」[3]라고 한다.

아텐신의 변모[편집]

아텐신은 동물적, 인간적 형태인 다른 이집트의 신들과는 달리, 첨단이 손의 형상을 취득하는 태양광선을 몇개나 발해, 광선의 하나에 생명의 상징 앙크를 잡은 태양 원반의 형태로 표현되었다[4]. 또 아텐신은 평화와 은혜의 신으로 여겨졌다[5].

아마르나 미술[편집]

사실을 있는 그대로에 드러내는 태양광선을 우러러보기 위해, 미술에서도 사실적인 표현을 해 아마르나 시대의 미술 양식은 「아마르나 양식」이라고 불려 다른 시대의 이집트 미술과는 구별을 분명히 한 것이 되고 있다.

임종[편집]

종교개혁의 실패[편집]

이 종교 개혁은 너무 급격했기 때문에, 아멘신단의 저항이 격렬하고, 최종적으로 실패에 끝났다. 아멘호테프 4세 아크엔아텐이 실의 가운데 죽은 후, 그 아들인 투탕카멘 왕의 시대에 이집트는 아멘 신앙으로 돌아왔다. 아텐은 아마르나 혁명 이전의 「천체로서의 태양」에 되돌려져 아텐 신앙은 소멸했다.

유일신기원설[편집]

프로이트는 아크엔아텐의 치세년과 출애굽의 해로 추정되는 연대가 거의 같은 일을 근거로, 아텐신이 같은 유일신교인 유태교의 신 야웨의 원형으로 하는 설[6]을 주창했다.

※ 아텐은 이걸로 안 되는데... 시간이 너무 없다. 어서 자야 해서.

아문

| 아문 | |||||

| 신들의 왕이자 바람의 신 | |||||

이집트 신왕국 시대의 아문의 묘사. 머리에 두 개의 기둥 장식을 쓰고 있다.※ 기둥?? plume을 해석한 것 같은데, 기둥이 아니라 '깃털'이다. | |||||

| 이름의 신성문자 표기 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 신앙중심지 | 테베 | ||||

| 상징 | 두 개의 기둥※ 깃털, 양머리 스핑크스 | ||||

| 성별 | 남신 | ||||

| 배우자 | 아무네트, 우스레트, 무트 | ||||

| 자식 | 콘수 | ||||

아문 (Amun 또는 아몬 Amon, 암몬 Ammon, 아멘 Amen)은 고대 이집트 신화의 신의 이름으로서 "숨겨진" 이라는 뜻을 갖고 있다. 아문은 이집트의 나일강 상류에 위치한 테베에서 숭배되던 바람과 공기의 신으로서 후에 태양신 라(레)와 합쳐진 후 아문-라 또는 아문-레로서 태양을 상징하는 신으로 자리를 잡은 것으로 보인다. 그 후 기독교에서 기도가 끝나고 외치는 아멘의 어원이 되었다는 설도 있다. 마케도니아의 알렉산더 대왕은 이집트에 입성한 기원전 332년, 고대 이집트의 문명을 보고 스스로를 ‘아문의 아들’이라고 칭하였다. 아문은 주요 신이기 때문에 그리스인들은 제우스, 로마인들은 주피터와 동일시하였다.

After the rebellion of Thebes against the Hyksos and with the rule of Ahmose I, Amun acquired national importance, expressed in his fusion with the Sun god, Ra, as Amun-Ra or Amun-Re.

Amun-Ra retained chief importance in the Egyptian pantheon throughout the New Kingdom (with the exception of the "Atenist heresy" under Akhenaten). Amun-Ra in this period (16th to 11th centuries BC) held the position of transcendental, self-created[2]creator deity "par excellence", he was the champion of the poor or troubled and central to personal piety.[3] His position as King of Gods developed to the point of virtual monotheism where other gods became manifestations of him. With Osiris, Amun-Ra is the most widely recorded of the Egyptian gods.[3] As the chief deity of the Egyptian Empire, Amun-Ra also came to be worshipped outside of Egypt, in Ancient Libya and Nubia, and as Zeus Ammon came to be identified with Zeus in Ancient Greece.

Early history

Amun and Amaunet are mentioned in the Old Egyptian Pyramid Texts.[4] Amun and Amaunet formed one quarter of the ancient Ogdoad of Hermopolis. The name Amun (written imn, pronounced Amana in ancient Egyptian [5]) meant something like "the hidden one" or "invisible".[6] It was thought that Amun created himself and then his surroundings.[7]

The other members of the Ogdoad are Nu and Naunet; Kuk and Kauket; and Huh and Hauhet.

Amun rose to the position of tutelary deity of Thebes after the end of the First Intermediate Period, under the 11th dynasty. As the patron of Thebes, his spouse was Mut. In Thebes, Amun as father, Mut as mother and the Moon god Khonsu formed a divine family or "Theban Triad".

New Kingdom

Further information: High Priests of Amun

Identification with Min and Ra

When the army of the founder of the Eighteenth dynasty expelled the Hyksos rulers from Egypt, the victor's city of origin, Thebes, became the most important city in Egypt, the capital of a new dynasty. The local patron deity of Thebes, Amun, therefore became nationally important. The pharaohs of that new dynasty attributed all their successful enterprises to Amun, and they lavished much of their wealth and captured spoil on the construction of temples dedicated to Amun.

The victory accomplished by pharaohs who worshipped Amun against the "foreign rulers", brought him to be seen as a champion of the less fortunate, upholding the rights of justice for the poor.[3] By aiding those who traveled in his name, he became the Protector of the road. Since he upheld Ma'at (truth, justice, and goodness),[3] those who prayed to Amun were required first to demonstrate that they were worthy by confessing their sins. Votive stelae from the artisans' village at Deir el-Medina record:

Subsequently, when Egypt conquered Kush, they identified the chief deity of the Kushites as Amun. This Kush deity was depicted as ram-headed, more specifically a woolly ram with curved horns. Amun thus became associated with the ram arising from the aged appearance of the Kush ram deity. A solar deity in the form of a ram can be traced to the pre-literate Kerma culture in Nubia, contemporary to the Old Kingdom of Egypt. The later (Meroitic period) name of Nubian Amun was Amani, attested in numerous personal names such as Tanwetamani, Arkamani, Amanitore, Amanishakheto, Natakamani. Since rams were considered a symbol of virility, Amun also became thought of as a fertility deity, and so started to absorb the identity of Min, becoming Amun-Min. This association with virility led to Amun-Min gaining the epithet Kamutef, meaning Bull of his mother,[10] in which form he was found depicted on the walls of Karnak, ithyphallic, and with a scourge, as Min was.

| Amun-Ra in hieroglyphs |

|---|

"Lord of truth, father of the gods, maker of men, creator of all animals, Lord of things that are, creator of the staff of life."[11]As the cult of Amun grew in importance, Amun became identified with the chief deity who was worshipped in other areas during that period, the sun god Ra. This identification led to another merger of identities, with Amun becoming Amun-Ra. In the Hymn to Amun-Ra he is described as

"Lord of truth, father of the gods, maker of men, creator of all animals, Lord of things that are, creator of the staff of life."[11]

※ 아문도 할 것 많은데... ㅜㅠ

무트

| 무트 | |||||

| 천공의 신이자 여왕·왕비의 신 | |||||

| |||||

| 이름의 신성문자 표기 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 신앙중심지 | 테베 | ||||

| 상징 | 대머리수리 | ||||

| 성별 | 여신 | ||||

| 배우자 | 아문 | ||||

| 부모 | 자연발생함 | ||||

| 자식 | 콘수 | ||||

무트(Mut, Maut, Mout)는 고대 이집트의 모(母)신이다. 고대 이집트어 '어머니'에서 파생된 여신의 이름을 통해 볼 수 있듯이 무트는 신들의 어머니, 하늘의 여주인, 여신들의 여왕, 지구의 어머니, 라의 눈, 스스로 태어난 자 등으로 불리었다.

이름[편집]

고대 이집트어의 어머니라는 뜻이다.

신화[편집]

신왕국(新王國)시대의 테베에서 주신(主神) 아몬(Amon)의 아내가 되어 아들 콘수(Khonsu)와 함께 삼신일좌(三神一座)의 짝을 이루었다. 테베의 나일강(江) 건너편 카르나크에 있는 아몬 신전(神殿)과 콘수 신전 가까이에 무트 신전이 있는데, 특히 아멘호테프 3세(?∼BC 1379) 때 많이 축조되었다. 무트는 고대 이집트 말로 '어머니·밭'을 뜻하고, 상형문자(象形文字)로는 동음(同音)인 대머리 독수리의 모습으로 표현된다.

아몬이 하늘의 주신이 된 뒤 태양의 여신, 하늘의 여신이 되었다. 이 때문에 동방 세계의 여주인 바스트(Bast), 파괴와 재생의 여신 세크메트(Sekhmet)와 혼동되기도 하는데, 사자의 머리와 고양이의 모습으로 나타나는 것은 이 때문이다. 보통 독수리 형태를 한 모자를 머리에 쓰거나 쌍관을 얹은 가발을 쓴 여성의 모습으로 표현된다.

같이 보기[편집]

Changes of mythological position[edit]

Mut was a title of the primordial waters of the cosmos, Naunet, in the Ogdoad cosmogony during what is called the Old Kingdom, the third through sixth dynasties, dated between 2,686 to 2,134 BCE. However, the distinction between motherhood and cosmic water later diversified and lead to the separation of these identities, and Mut gained aspects of a creator goddess, since she was the mother from which the cosmos emerged.

※ 음. 다른가? 태초의 대양 누트의 여성형인 나우네트와 우주의 어머니 무트의 역할을 사뭇 비슷한 것도 같은데.

The hieroglyph for Mut's name, and for mother itself, was that of a vulture, which the Egyptians believed were very maternal creatures. Indeed, since Egyptian vultures have no significant differing markings between female and male of the species, being without sexual dimorphism, the Egyptians believed they were all females, who conceived their offspring by the wind herself, another parthenogenic(처녀생식) concept.

※ 대머리 독수리라 그런지도. 대머리는 남성의 상징인데, 생물학적인 암컷 독수리의 머리가 대머리라 그렇게 여겼는지도 모르겠네. 어라? 대머리 독수리인데 새끼를 낳네? 대머리지만 전부 암컷이로군! 이러며.

Much later new myths held that since Mut had no parents, but was created from nothing; consequently, she could not have children and so adopted one instead. ※ 이건 이상하다. 남신인 아툼도 무에서 태어났지만 자식들을 만들었는데.

Making up a complete triad of deities for the later pantheon of Thebes, it was said that Mut had adopted Menthu, god of war. This choice of completion for the triad should have proved popular, but because the isheru, the sacred lake outside Mut's ancient temple in Karnak at Thebes, was the shape of a crescent moon, Khonsu, the moon god eventually replaced Menthu as Mut's adopted son.

Lower and upper Egypt both already had patron deities–Wadjet and Nekhbet–respectively, indeed they also had lioness protector deities–Bast and Sekhmet–respectively. When Thebes rose to greater prominence, Mut absorbed these warrior goddesses as some of her aspects. First, Mut became Mut-Wadjet-Bast, then Mut-Sekhmet-Bast (Wadjet having merged into Bast), then Mut also assimilated Menhit, who was also a lioness goddess, and her adopted son's wife, becoming Mut-Sekhmet-Bast-Menhit, and finally becoming Mut-Nekhbet.

Later in ancient Egyptian mythology deities of the pantheon were identified as equal pairs, female and male counterparts, having the same functions. In the later Middle Kingdom, when Thebes grew in importance, its patron, Amun also became more significant, and so Amaunet, who had been his female counterpart, was replaced with a more substantial mother-goddess, namely Mut, who became his wife. In that phase, Mut and Amun had a son, Khonsu, another moon deity.

The authority of Thebes waned later and Amun was assimilated into Ra. Mut, the doting mother, was assimilated into Hathor, the cow-goddess and mother of Horus who had become identified as Ra's wife. Subsequently, when Ra assimilated Atum, the Ennead was absorbed as well, and so Mut-Hathor became identified as Isis (either as Isis-Hathor or Mut-Isis-Nekhbet), the most important of the females in the Ennead (the nine), and the patron of the queen. The Ennead proved to be a much more successful identity and the compound triad of Mut, Hathor, and Isis, became known as Isis alone—a cult that endured into the 7th century A.D. and spread to Greece, Rome, and Britain.

Depictions[edit]

In art, Mut was pictured as a woman with the wings of a vulture, holding an ankh, wearing the united crown of Upper and Lower Egypt and a dress of bright red or blue, with the feather of the goddess Ma'at at her feet.

Alternatively, as a result of her assimilations, Mut is sometimes depicted as a cobra, a cat, a cow, or as a lioness as well as the vulture.

Before the end of the New Kingdom almost all images of female figures wearing the Double Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt were depictions of the goddess Mut, here labeled "Lady of Heaven, Mistress of All the Gods." The last image on this page shows the goddess's facial features which mark this as a work made sometime between late Dynasty XVIII and relatively early in the reign of Ramesses II (circa 1279-1213 B.C.).[2]

In Karnak[edit]

There are temples dedicated to Mut still standing in modern-day Egypt and Sudan, reflecting the widespread worship of her, but the center of her cult became the temple in Karnak. That temple had the statue that was regarded as an embodiment of her real ka. Her devotions included daily rituals by the pharaoh and her priestesses. Interior reliefs depict scenes of the priestesses, currently the only known remaining example of worship in ancient Egypt that was exclusively administered by women.

Usually the queen, who always carried the royal lineage among the rulers of Egypt, served as the chief priestess in the temple rituals. The pharaoh participated also and would become a deity after death. In the case when the pharaoh was female, records of one example indicate that she had her daughter serve as the high priestess in her place. Often priests served in the administration of temples and oracles where priestesses performed the traditional religious rites. These rituals included music and drinking.

The pharaoh Hatshepsut had the ancient temple to Mut at Karnak rebuilt during her rule in the Eighteenth Dynasty. Previous excavators had thought that Amenhotep III had the temple built because of the hundreds of statues found there of Sekhmet that bore his name. However, Hatshepsut, who completed an enormous number of temples and public buildings, had completed the work seventy-five years earlier. She began the custom of depicting Mut with the crown of both Upper and Lower Egypt. It is thought that Amenhotep III removed most signs of Hatshepsut, while taking credit for the projects she had built.

Hatshepsut was a pharaoh who brought Mut to the fore again in the Egyptian pantheon, identifying strongly with the goddess. She stated that she was a descendant of Mut. She also associated herself with the image of Sekhmet, as the more aggressive aspect of the goddess, having served as a very successful warrior during the early portion of her reign as pharaoh. ※ 역시 하트셉수트♥

Later in the same dynasty, Akhenaten suppressed the worship of Mut as well as the other deities when he promoted the monotheistic worship of his sun god, Aten. Tutankhamun later re-established her worship and his successors continued to associate themselves with Mut afterward.

Ramesses II added more work on the Mut temple during the nineteenth dynasty, as well as rebuilding an earlier temple in the same area, rededicating it to Amun and himself. He placed it so that people would have to pass his temple on their way to that of Mut.

Kushite pharaohs expanded the Mut temple and modified the Ramesses temple for use as the shrine of the celebrated birth of Amun and Khonsu, trying to integrate themselves into divine succession. They also installed their own priestesses among the ranks of the priestesses who officiated at the temple of Mut.

The Greek Ptolemaic dynasty added its own decorations and priestesses at the temple as well and used the authority of Mut to emphasize their own interests.

Later, the Roman emperor Tiberius rebuilt the site after a severe flood and his successors supported the temple until it fell into disuse, sometime around the third century A.D. Some of the later Roman officials used the stones from the temple for their own building projects, often without altering the images carved upon them.

Personal piety[edit]

In the wake of Akhenaten's revolution, and the subsequent restoration of traditional beliefs and practices, the emphasis in personal piety moved towards greater reliance on divine, rather than human, protection for the individual. During the reign of Rameses II a follower of the goddess Mut donated all his property to her temple and recorded in his tomb:

콘수

| 콘수 | ||||||

| 젊음과 달의 신 | ||||||

인간의 모습을 한 콘수. 콘수는 매의 머리로 그려질 때도 있다. | ||||||

| 이름의 신성문자 표기 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 신앙중심지 | 테베 | |||||

| 상징 | 달 원반 | |||||

| 성별 | 남신 | |||||

| 부모 | 아문과 무트 또는 바스테트와 아누비스 | |||||

콘수(Khonsu, Chonsu, Khensu, Khons, Chons, Khonshu)는 고대 이집트 신화에 등장하는 달의 신이다. 콘수라는 이름은 고대 이집트의 '여행하다'라는 단어에서 파생되었다. 후에 달의 신이라는 개념은 토트에게 옮겨졌다. Khonsu was instrumental in the creation of new life in all living creatures. At Thebes he formed part of a family triad (the "Theban Triad") with Mut as his mother and Amun his father.

같이보기[편집]

바깥고리[편집]

Mythology[edit]

His name reflects the fact that the Moon (referred to as Iah in Egyptian) travels across the night sky, for it means "traveller", and also had the titles "Embracer", "Pathfinder", and "Defender", as he was thought to watch overnight travellers. As the god of light in the night, Khonsu was invoked to protect against wild animals, and aid with healing. It was said that when Khonsu caused the crescent moon to shine, women conceived, cattle became fertile, and all nostrils and every throat was filled with fresh air.

"Khonsu" can also be understood to mean "king's placenta", and consequently in early times, he was considered to slay the king's (i.e. the pharaoh's) enemies, and extract their innards for the king's use, metaphorically creating something resembling a placenta for the king. This bloodthirsty aspect leads him to be referred to, in such as the Pyramid texts, as the "(one who) lives on hearts". He also became associated with more literal placentas, becoming seen as a deification of the royal placenta, and so a god involved with childbirth.

※ 이 부분 이전에 스터디했던 기억 나는데... 구체적인 내용을 다 잊어버렸다. -_ㅜ

Attributes[edit]

Khonsu is typically depicted as a mummy with the symbol of childhood, a sidelock of hair, as well as the menat necklace with crook and flail. He has close links to other divine children such as Horus and Shu. He is sometimes shown wearing a falcon's head like Horus, with whom he is associated as a protector and healer, adorned with the sun disk and crescent moon.[1]

He is mentioned in the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts, in which he is depicted in a fierce aspect, but he does not rise to prominence until the New Kingdom, when he is described as the "Greatest God of the Great Gods". Most of the construction of the temple complex at Karnak was centered on Khonsu during the Ramesside period.[1] His temple at Karnak is in a relatively good state of preservation, and on one of the walls is depicted a cosmogeny in which Khonsu is described as the great snake who fertilizes the Cosmic Egg in the creation of the world.[2]

Khonsu's reputation as a healer spread outside Egypt; a stele records how a princess of Bekhten was instantly cured of an illness upon the arrival of an image of Khonsu.[3] King Ptolemy IV, after he was cured of an illness, called himself "Beloved of Khonsu Who Protects His Majesty and Drives Away Evil Spirits".

Locations of Khonsu's cult were Memphis, Hibis and Edfu.[1]

Evolution[edit]

| ||||||||||||

| Khonsu of Thebes The "Maker" of men's destinies – Chonsu-pa-âri-sekher-em-"Uas-t" in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Khonsu gradually replaced the war-god Monthu as the son of Mut in Theban thought during the Middle Kingdom, because the pool at the temple of Mut was in the shape of a crescent moon. The father who had adopted Khonsu was thought to be Amun, who had already been changed into a more significant god by the rise of Thebes, and had his wife changed to Mut. As these two were both considered extremely benign deities, Menthu gradually lost his more aggressive aspects.

In art, Khonsu was depicted as a man with the head of a hawk, wearing the crescent of the new moon subtending the disc of the full moon. His head was shaven except for the sidelock worn by Egyptian children, signifying his role as Khonsu the Child. Occasionally he was depicted as a youth holding the flail of the pharaoh, wearing a menat necklace. He was sometimes pictured on the back of a goose, ram, or two crocodiles. His sacred animal was the baboon, considered a lunar animal by the ancient Egyptians.

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c "The Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology", Edited by Donald B. Redford, pp. 186–187, Berkley, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- ^ Handbook of Egyptian Mythology, Geraldine Pinch, p156, ABC-CLIO, 2002, ISBN 1-57607-242-8

- ^ This incident is mentioned in the opening of chapter one of Bolesław Prus' 1895 historical novel Pharaoh.